The Krakow Ghetto (officially known as Der jüdische Wohnbezirk in Krakau in German, which means 'The Jewish residential district in Krakow’ and 'Krokewer geto’ in Yiddish) was a ghetto established for the Jewish population in Krakow by the German occupying authorities in the Podgórze district in March 1941.

Before World War II set the world on fire, around 64,000 Jews called Krakow their home. These individuals weren’t just situated in one corner of the city – they were all over the place. The areas with the most Jewish inhabitants were the Kazimierz district, the historic Jewish district of Krakow, Stradom, and Podgórze. In terms of numbers, this vibrant community was the fourth largest of its kind in Poland.

Let me remind you that on September 6, 1939, the German army marched into Krakow. Merely days later, the lives of these Jews turned into a nightmare as the German oppressors introduced a string of cruel bans and orders. Jewish prayers in synagogues were no longer allowed. Jewish doctors and lawyers were forbidden to serve Aryans. If you were a Jew, you wouldn’t be allowed to do ritual slaughter, use public transport, or even access the Market Square and Planty Park areas. Your property would be taken away, your schools would be shut down, and your places of worship desecrated.

I think it’s worth to say that, faced with these horrors, Jews started moving in greater numbers to Kazimierz and Stradom. Here, displaced people, those removed from their homes in old town by the occupiers, sought refuge. Jews from other cities like Łódź, Kalisz, Warsaw, as well as from the rural areas of the Krakow Province, also poured in, hoping to find a safe haven.

↳ Make sure to read my guide to the most amazing places to stay in Kraków:

How to Find Best Place to Stay in Krakow Old Town – Your Guide

Because of this mass migration, the Jewish population in Krakow quickly grew. The data I found says that during the first few months of the occupation, it shot up from 64,000 to 68,000 people registered in the Jewish Community and continued to grow until the latter half of 1940.

Krakow Ghetto – The Symbol of Oppression

From December 1, 1939, every Jew above the age of 12 was required to wear an armband adorned with the Star of David. I know this might seem hard to believe, but the Jewish community ended up distributing nearly 55,000 of these wristbands.

Kraków 1940-1941

If you’re interested in dark figures from history, here’s one – Hans Frank, the Governor residing in Krakow. This man desired the capital of the General Government to „handle” the „Jewish problem” in an „exemplary” manner. Being there, you need to know that his vision of „handling” involved initiating mass deportations to the Lublin district in the second half of 1940. Unfortunately, most of these Jews were sent to their doom – between 1942 and 1943, they were murdered in the camps in Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka.

The Birth of the Krakow Ghetto

On March 3, 1941, Dr. Otto Wächter, the governor of the Kraków district, issued an order that marked a significant and tragic milestone in Krakow’s history. This order initiated the creation of the Krakow Ghetto, with the opening date set for March 21.

Let’s take a moment to visualize the location of this place. The Ghetto was set up in the Podgórze district, covering an area of approximately 20 hectares. It included 15 streets, or fragments of streets, and 320 houses – mainly single-story or double-story houses. The borders of the ghetto stretched from the Podgórski Market Square to the streets of Krzemionki and Traugutta, Kącik, Nadwiślańska, Wita Stwosza, and Brodzińskiego. Barbed wire originally encircled the entire district, which was later replaced with a wooden fence.

The order outlined a plan for the resettlement of Jews to the Podgórze Ghetto and Poles to Kazimierz. This colossal task was to be completed within a span of just 18 days, from March 3 to 20. By the end of March 20, all Jews previously living in Kraków were expected to be inside the boundaries of the ghetto. Jewish businesses, workshops, and shops situated outside the ghetto were allowed to continue operation.

A Closer Look at the Ghetto Life

During this upheaval, Jews were allowed to bring their movable belongings into the ghetto, excluding anything that the Germans might find useful. Leftover items were to be surrendered to the Trust Office, which supposedly granted permission to sell these items. I can tell you that this was nothing more than an empty promise, as the Trust Office never actually granted such permissions.

Living within the confines of the Ghetto came with its own set of stringent rules. Leaving the ghetto required a special permit for Jews, while non-Jews needed a pass issued by the authorities to enter. On top of this, there was a ban on providing Jews with any form of shelter, even temporarily.

As the days passed, the rest of the Jews from Kazimierz and other Krakow districts were forcefully moved into the ghetto. An area that originally housed about 3,500 people now had to accommodate over 16,000! The population grew even larger in the fall of 1941, when Jews from the villages surrounding Kraków were also sent to the ghetto. On October 15, 1941, the district was officially designated a closed district, with anyone trying to leave without an appropriate pass risking a death sentence.

- You may also like to read: Death Sentence in Poland – The Dark Chapter of Last Execution in 1988

Behind the Ghetto Walls

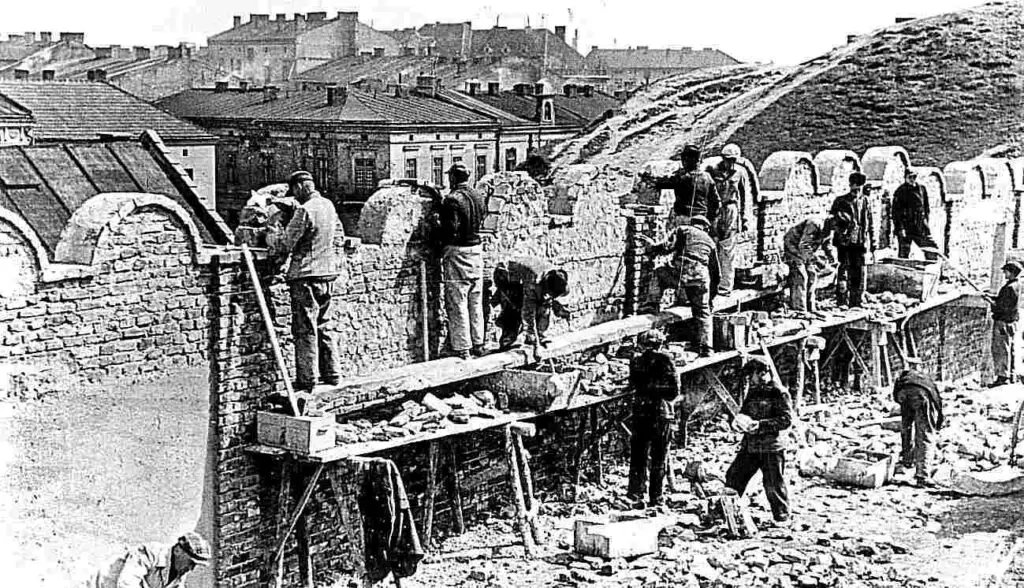

In April, the construction of a towering wall around the ghetto began. This wall, crowned with a motif of tombstones, symbolized the harsh and devastating life that awaited those condemned to live within. Four massive gates, coated with the same grey mortar as the wall, served as entry points to the ghetto. The windows of the houses on the Aryan side were either barred or bricked up.

Interestingly, two tram lines ran through the ghetto. But let me assure you, these trams weren’t there to help the residents. No stops were designated within the closed district, and none of the trams ever halted inside.

Life Behind the Ghetto Walls

During the initial months of the ghetto’s existence, contact between the ghetto residents and the rest of the city wasn’t overly problematic. It was fairly easy to obtain permits, which were used by Jews who worked outside the ghetto in Polish and German enterprises, or those who still managed to run their shops.

The ability to interact with the city allowed the ghetto inhabitants to obtain supplies. Anyone working outside the ghetto had the opportunity to buy food for themselves and their families. So, during this period, the Jews in the ghetto didn’t face severe hunger, and the cost of food was only slightly higher than on the „Aryan” side.

However, this situation dramatically changed when the German authorities decided to tighten the ghetto’s isolation. Food prices soared, quickly reaching levels that were multiple times higher than in the free market. The few shops located in the ghetto began to sell off their remaining supplies. They also distributed rations — a mere 100g of bread per person per day, and occasionally, some sugar. That was all the rations assigned to Jews.

The Struggle of Isolation

The isolation of the ghetto’s population worsened with the „Third Ordinance on Restrictions on Stay in the General Government” on October 15, 1941.

This directive threatened the death penalty for Jews leaving the ghetto and for anyone who sheltered them. A few weeks later, the Jewish population was stripped of the ability to use the post office.

Increasingly strict isolation led to the closure of Jewish shops and workshops located outside the ghetto. Their supply and even accessibility faced new challenges daily.

The Battle with Overcrowding

If you ask me what was the main issue in the ghetto, I’d say it was the astonishing overcrowding. According to the standards set by the housing commission operating in the ghetto, each person was allocated only 2 square meters of space. There was also a rule of 3 people per window, often resulting in even worse living conditions.

The Podgórze ghetto was devoid of greenery and situated far from the nearby Vistula River. The only place where people could get some fresh air was Plac Zgody. But let me tell you, during periods of relative calm and if the weather was decent, the square was so crowded that it resembled a demonstration site rather than a place to breathe easy.

According to the Krakow Jewish Community’s statistical list, on October 13, 1941, the ghetto’s population stood at 15,288 people. This included 1,200 unregistered individuals or those without ID cards. Out of this total, 13,970 people were crammed into 3,167 residential rooms. The rest, around 1,318 people, occupied collective spaces like orphanages and old people’s homes.

A Diminishing Ghetto Population

According to the „Die Stadt Krakau” bulletin, by the end of October, the ghetto’s population had grown to 19,000. However, living conditions took a turn for the worse after the „June deportations„, which saw around 5,000 people murdered, consequently reducing the size of the ghetto.

On June 20, 1942, Stadthauptmann Rudolf Pavlu further restricted the area of the Krakow ghetto. The space now extended from the right side of Limanowskiego Street in the north to Rekawka Street in the south, along with the southern sections of Węgierska and Krakusa Streets, and two short sections of Św. Benedict and Stefan Czarniecki. The severe overcrowding of the reduced district left the residents no choice but to leave their belongings in their deserted apartments.

Survival in the Face of Despair

The terror of death, occupiers brutally disregarding human dignity, poverty, and a sense of despair and hopelessness sparked extreme reactions among the people packed into these cramped apartments.

Particularly during displacement periods, a wave of suicides swept over the more vulnerable and elderly population. There were instances where, succumbing to the pleas of older family members, loved ones provided them with cyanide.

However, let me say this – the situation grew even more severe after another resettlement operation in October 1942, which further reduced the ghetto area, creating a region known as „Ukraine”.

Deportations and Horrors Unfold

At the end of May 1942, the occupying forces initiated large-scale operations in the Kraków region aimed at deporting the Jewish population to death camps. The ominous plans for the Krakow ghetto began taking shape on May 30 and 31, with a thorough inspection of identification cards. These cards could only be obtained through work certificates or bribes. Thousands of people were denied identification cards, which essentially translated into their expulsion.

On the night of May 31 to June 1, 1942, officers of the Jewish Community, with the help of OD men, began checking identification cards, apartment by apartment. People without valid cards were ordered to pack essential items and exit their homes.

The OD-men then escorted them to Plac Zgody. By the morning of June 1, about two thousand men, women, and children were gathered in Plac Zgody. Among those marked for deportation was the chairman of the Jewish Council, Dr. Artur Rosenzweig, and his family, condemned for allegedly inefficiently organizing the roundup in the square.

However, according to the Germans, the deportation executed on June 1 did not yield the desired effect. The Security Police was convinced that thousands of those slated for deportation had evaded the roundup. Thus, on the night of June 3-4, those without valid identification cards were arrested throughout the ghetto again.

On the morning of Thursday, June 4, police units swung into action. The displaced individuals gathered at Plac Zgody were hurriedly escorted by SS guards to Prokocim. The procession route was marked by the bodies of those who fell, unable to keep pace, under the bullets of the escorts. At the station, a train was ready, destined for the east.

Two days after the events of this „Bloody Thursday”, on June 6, the security police undertook yet another operation aimed at reducing the number of ghetto inhabitants. All existing permits or work certificates were revoked. In their stead, the German authorities introduced the „Blauschein” (blue card), which alone, as an attachment to the identification card, confirmed the right to stay in the ghetto. Those denied a blue card were instantly detained and led in groups to the courtyard of Optima, with no chance to bid their families goodbye or pack anything for the journey.

On Monday, June 8, they were dispatched under guard from Optima to Prokocim and from there by freight train to Bełżec. The June deportations, the first part of „Operation Reinhard” in the Krakow region, claimed over 5,000 lives. Many, particularly the young ones, voluntarily went into „exile”, unwilling to part from their relatives who had been denied a residence permit.

On the evening of October 27, 1942, the ghetto area was surrounded by a thick chain of security police stations, hinting at the horrors yet to unfold.

The Night of Horror and Further Deportations

As darkness descended, the Jewish police force (ODs) started raiding homes, dragging out individuals based on precompiled lists. The displaced persons, assembled in groups, were rapidly ushered to Plac Zgody, where they were ordered to sit on the ground and wait. Those gathered were subjected to a selection process, this time devoid of any criteria based on age, employment type or skillset.

Physical appearance seemed to be the decisive factor, but even that wasn’t a rule, because alongside the elderly and weak, young and strong individuals were also singled out for „deportation”. The campaign didn’t spare anyone, including patients from the hospital and children from the orphanage.

Several hundred people were brutally murdered on the spot, and approximately 4,500 were deported to Bełżec. The boundaries of the ghetto shrank yet again, with Lwowska Street becoming the new border.

Towards the end of the year, the ghetto was split into two parts – „A” and „B”. „A” was designated for those still capable of work, whereas „B” was meant for the inhabitants deemed unfit for labor, namely children, the elderly, and the sick, all of whom were condemned to extermination.

On the late afternoon of October 28, some of those gathered at Plac Zgody were transported via trucks, while the remainder were herded on foot to Płaszów. In the evening, a freight train teeming with „displaced persons” departed from the Kraków-Płaszów station, heading eastward. The number of victims transported that day to extermination camps or taken outside the city to be shot is estimated at around 6,000. The exact number of people killed on the spot remains unknown, with official sources citing a figure of 35.

The Judenrat (Jewish Council)

The Judenrat, or Jewish Council, in Kraków was established towards the end of 1939. Instead of holding elections, 13 new members were co-opted onto the existing 11-member board of the Jewish Community. The resulting composition received approval from city elder Schmidt, with police officer Brandt assigned to oversee the Council’s activities. The inaugural meeting of the Jewish Council of the city of Kraków took place in mid-February 1940.

The Council was primarily tasked with the meticulous and punctual execution of the recommendations, orders, and directives issued by the German authorities. These directives chiefly involved conducting fresh census counts of the Jewish poppulation, aiding in relocation operations, and orchestrating deportations to forced labor or extermination camps. Internally, within the districts inhabited by Jews, the Council managed matters pertaining to supplies, social welfare, and aid for refugees, as well as health and medical assistance.

The Council also kept records, organized registry offices, maintained cemeteries, and from August 1940, was charged by the German authorities with the organization and oversight of primary and vocational education.

Initially, the Jewish Council oversaw the Jewish Order Service (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst, OD), which was established in the summer of 1940.

However, before long, its commander, Symche Spira, became independent of the Council, transforming the OD into a gang of criminals that preyed upon the inhabitants of the ghetto, especially during deportations.

Following the deportation of the Chairman of the Jewish Council, Dr. A. Rosenzweig, on June 1, 1942, the German authorities dissolved the Council and established a trusteship for the ghetto. The commissar of the ghetto was Dawid Gutter from Tarnów, assisted by a bodyguard appointed by the Germans.

Institutions and Hospitals Within the Ghetto Boundaries

When the ghetto was established, all Jewish institutions in Krakow were squeezed within its confines. The Jewish Community offices found a home at 2 Limanowskiego Street. The Jewish Social Self-Help was given space in the Podgórze branch of Komunalna Kasa Oszczędności at Józefińska Street, the lone representative building in the district.

The orphanage, previously housed in a tenement building on Dietl Street, was necessitated to relocate to 8 Krakusa Street, a building that quickly proved too small for its needs.

Organizing a hospital and other health facilities proved to be a particularly challenging issue within the densely crowded ghetto. The main hospital, once the pride of the Jewish community of Krakow, was evacuated from Skawińska Street and squeezed into 14 Józefińska Street, a previously neglected and cramped tenement building formerly used by the blue police and the tax office. Renovation work, financed by the ghetto residents, continued until October 1941. The renovated building, boasting 30 rooms, housed the following departments:

- Internal

- Surgical

- Gynecological and Obstetrics

- Specialist Clinics

- Clinics and Laboratories

Overall, the hospital offered 120 beds and was equipped with an operating room and a laboratory.

Throughout its existence, the hospital at 14 Józefińska Street was continuously overcrowded. In addition to serving the local ghetto residents, it provided medical services to the Jewish population from ghettos in neighboring towns and Jews from the labor camp in Płaszów and its sub-camps in Prokocim, Bieżanów, and Podgórze on Wielicka Street. The growing poverty among the ghetto inhabitants led to a rise in sickness, and the gates of other hospitals were barred to Jews.

In an attempt to at least partially alleviate the severe overcrowding at the hospital, a community service was set up for the elderly, the disabled, and the chronically ill at 15 Limanowskiego Street. Of all the health facilities, only the infectious diseases hospital at 30 Rekawka Street did not need to change its location for the time being, as the street fell within the ghetto boundaries.

Liquidation of the Ghetto

In February 1943, the German authorities executed a division of the ghetto into part 'A’, reserved for the working population, and part 'B’ for the non-working, the sick, and the weak. Transition between the two parts was possible only with a special pass, granted solely in exceptional circumstances.

Another portent of the imminent liquidation of the Jewish quarter came with the appointment of SS-Untersturmführer Amon Göth as the commandant of the Płaszów labor camp.

In the first days of March, Göth instructed the ghetto authorities to relocate the residents of ghetto 'A’ to the Płaszów concentration camp. The actions of Commissioner Gutter failed to satisfy the Germans, which was likely a calculated intention. On Saturday, March 13, 1943, at 11:00 a.m., the Commissioner of the Jewish district received a new written order: SS and police commander J. Scherner commanded:

- 1) The residents of Ghetto 'A’ were to resettle to the Płaszów camp on March 13, at 5:00 p.m.

- 2) The residents of Ghetto 'B’ were to assemble on March 14 at Plac Zgody with the notice that they would be redirected to the barracks of the Ostbahn company, where they would commence work.

The news of the ghetto’s liquidation hit the people like a lightning bolt. The six-hour resettlement deadline made seeking refuge outside the ghetto practically impossible. The horror and despair were amplified by the sight of heavily armed soldiers stationed in tight cordons at Plac Zgody and the streets and passages leading to the walls of the ghetto.

In desperation, numerous inhabitants attempted escape through the sewers. Only the initial groups succeeded; the others fell into the hands of the police near the canal manhole in the area of the railway bridge in Zabłocie. After 11 o’clock, the action commander, SS-Sturmbannführer Willi Haase, arrived in the ghetto, accompanied by Amon Göth. A company of Ukrainians followed them, and SS patrols manned the streets.

The barbed-wire fence dividing the ghetto demarcated the boundary between the inhabitants of Ghetto 'A’, destined for Płaszów, and the inhabitants of Ghetto 'B’, sentenced to extermination. Within a few hours, the working ghetto was emptied.

The following day, Sunday, March 14, 1943, from dawn, groups of people expelled from apartments in Ghetto 'B’ began to arrive at Plac Zgody.

The Jewish Order Service (OD) began the grim task of assembling separate groups of men, elderly, women, and children, joined by the older children from the orphanage.

At an unexpected moment, gunshots rang out into the helpless, terrified crowd. The first casualties fell, and soon the entire ghetto echoed with the relentless sound of gunfire. Individuals were methodically murdered, following a premeditated plan.

The youngest children, transported by flatcars, met their cruel end in the hall of the so-called „Dom Pierzaków” at ul. Nadwiślańska. Children ushered from Zgody Square to this grim destination suffered the same fate. Elderly individuals of both sexes were shot in the hallways and courtyards of houses around Zgody Square and in the streets during futile attempts to escape. In the surgical and infectious diseases hospitals, all the sick were shot in their beds, in rooms, corridors, and in the yard. Several hospital staff also met their end.

Once the gunfire subsided, Göth initiated a selection process, seeking roughly 200 skilled workers for the Płaszów camp. Tragically, a similar but much larger selection took place among those destined for Płaszów, removing all those who did not possess the required identification.

Around the 14th, all those condemned to extermination were prepared for transportation. They were herded onto trucks, urged on by the shouts of the accompanying SS men. Just before departure, a group of prisoners brought from the Jewish Order Service detention centers joined them. Under a heavy motorcycle escort, a cavalcade of several dozen trucks journeyed to Auschwitz, where the entire transport was sent directly to the gas chambers.

Including the people deported to Auschwitz and the final group ushered from Plac Zgody towards Płaszów, approximately 3,000 individuals—men, women, the elderly, and children—fell victim to the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto on March 13 and 14, 1943.

During those two fateful days, about 6,000 people were sent to the Płaszów camp. The occupation authorities now tied their fate with the existence of the Arbeitslager in Płaszów.

Final Words

Just before September 1, 1939, the Jewish population of Krakow numbered 64,000. Out of this, fewer than 1,000 individuals survived the occupation—in camps, in hiding, or with „Aryan” papers. The remainder, approximately 63,000, fell victim to „Operation Reinhard”, which in total claimed the lives of around six million Jews from Poland and other European countries, either through murder or gas chambers in Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

Simultaneously, all movable and immovable Jewish property was looted or deliberately destroyed, including the centuries-old achievements of Jewish culture and art.

References:

- https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getto_krakowskie

- https://www.jhi.pl/artykuly/13-marca-rocznica-likwidacji-getta-w-krakowie,579

- https://ipn.gov.pl/pl/aktualnosci/39182,Cztery-wielkie-bramy-opowiesc-o-krakowskim-getcie.html