Hey there! If you’re an art enthusiast or even if you’re just looking for an amazing place to spend an afternoon, the Krakow National Museum is a must-visit spot. Established in 1879, it’s not only the oldest, but also the largest museum with the „national” tag in Poland. Now, with over 900,000 exhibits, it reels in up to a million visitors every year.

So, let me tell you a little backstory of this iconic museum. In the late 19th century, during the grand-scale celebration of the 50th anniversary of Józef Ignacy Kraszewski’s creative work, the idea of a national museum sprang up. It was a patriotic era and Krakow, with its rich historical background and memories was the perfect spot for this cultural institution. The objective? To keep the patriotic spirit alive. It was on October 7, 1897, the Krakow National Museum was officially established.

The Birth Of The Museum Collection

Here’s a interesting fact – the museum’s collection all started with one painting. Yes, you heard it right. A painting by Henryk Siemiradzki called „Nero’s Torches” was generosly donated during the jubilee celebrations. Now, this wasn’t just any painting. It held a symbolic meaning and marked the beginning of the museum’s collection. Inspired by this gesture, other renowned artists also donated their masterpieces. This kickstarted the museum’s collection with works from artists like Juliusz Kossak and Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz.

Today, if you want to relive history and experience art like never before, I believe the Krakow National Museum is your go-to place. Its first headquarters were the Sukiennice, where you can still marvel at the Gallery of Polish Art of the 19th century.

↳ Make sure to read my guide to the most amazing places to stay in Kraków:

How to Find Best Place to Stay in Krakow Old Town – Your Guide

„Nero’s Torches” by Henryk Siemiradzki, 1876

Now, if there’s one artwork that you need to see at the museum, it’s „Nero’s Torches”. The painting started it all, and it’s listed as number 1 in the museum’s inventory book.

The monumental painting measures a whopping 385 x 704 cm and depicts the ruthless persecution of the first Christians by Emperor Nero in AD 64.

The scene, painted by Siemiradzki, captures the moment right before Nero lights the torches tied to the martyrs. The contrast between the powerless victims and the extravagantly dressed aristocrats creates a striking image.

The details and elements in this painting are impressively intricate, making it a visual feast. In fact, „Nero’s Torches” bagged a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878, catapulting Siemiradzki to fame. It’s worth to say that the painting toured many European cities and is a piece of art that deserves to be appreciated in person.

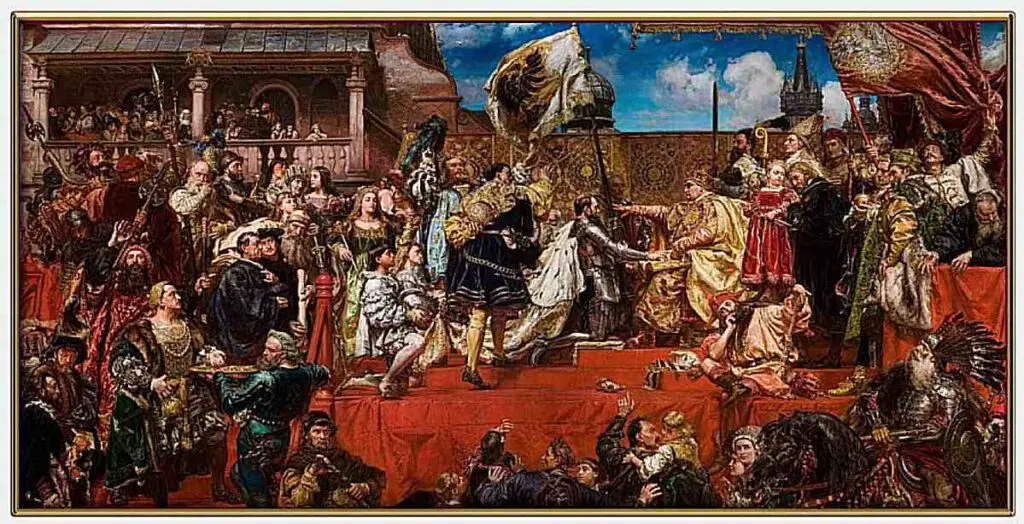

„The Prussian Homage” by Jan Matejko, 1879–1882

Now, if you know a thing or two about Polish art, you’d agree with me when I say that Jan Matejko is a name that resonates powerfully. He was a Krakow native and despite studying at foreign academies, he always found his way back home. He gained fame for his meticulous historical paintings. Let me say, it’s almost as if he got as much pleasure from deep research as he did from painting.

One such monmental piece is „The Prussian Homage”, which you can witness at the Krakow National Museum. The creation of this piece began on Christmas Eve in 1879 and concluded three years later.

It portrays the feudal homage paid to Polish King Sigismund the Old by the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht Hohenzollern, on April 10, 1525.

The painting is not just a historical piece. It represents Matejko’s philosophical vision of the history of the Polish nation.

As you immerse yourself in this painting, you might need a moment to distinguish the individual figures in the densely populated composition. The center stage, however, draws your attention immediately with Sigismund I the Old, robed in gold. You’d see Albrecht Hohenzollern, kneeling before the king, armored up.

The canvas is adorned with about thirty historical figures, including Mikołaj Firlej, Bona Sforza, and Jadwiga Jagiellonka. A key character is Stańczyk, bearing the resemblance of Matejko himself, seeming reflective and resigned. The painting, while subtly symbolic, serves primarily to recall the glorious moments of the Commonwealth.

„Girl With Chrysanthemums” by Olga Boznańska, 1894

Alright, let’s take a step back from these monumental historical pieces and take in a more nostalgic piece by Olga Boznańska, titled „Girl with Chrysanthemums„. Now, I know, the contrast between this painting and the previous ones might be striking. But trust me, it’s a breath of fresh air.

This iconic artwork never fails to hypnotize us with the piercing black eyes of the young protagonist. Interestingly, it’s not the title chrysanthemums that grab your attention at first, but those intense eyes. The white flowers brighten the otherwise gray picture, emphasizing the innocence of the child. But don’t let this simplicity fool you. The painting holds a deep melancholic mood, lined with anxiety and secrets only known to the girl.

Boznańska painted „Girl with Chrysanthemums” when she was 29. She was in Munich at the time, continuing her artistic education. Despite being barred from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts because of her gender, she studied in private studios. The influence of Impressionism is evident in her work, particularly in the way she applied paint and brushstrokes.

Yet, she developed her own unique style, often noted for its dark, sometimes depressing colors. In almost every portrait by Boznańska, there’s a sense of undefined sadness, longing, and sometimes, weariness. Yet, it’s this very melancholy that pulls us towards her work. I think it’s the beauty in the sadness that makes these portraits so captivating.

„A Frenzy of Exultation” by Władysław Podkowiński, 1894

Władysław Podkowiński’s A Frenzy of Exultation indeed elicited a real frenzy among its audience when it was first exhibited at Zachęta in Warsaw on March 18, 1894. The display was an exhibition for this one painting.

A colossal nude artwork, measuring 310 × 275 cm, showcased a naked, red-haired woman astride a frenzied horse.

The painting incited an uproar, with the woman’s nudity and brazen pose deemed scandalous. The horse, too, received criticism for its demonic demeanor. Yet, as often happens with controversial works and events, A Frenzy of Exultation quickly propelled Podkowiński to fame. The infamous exhibition attracted thousands of spectators.

The concept of painting a naked woman on a raging horse had occurred to the artist a few years earlier during his stay in Paris. The vision "consumed Podkowiński and took away his peace", as per Stefan Laurysiewicz, a friend of the artist.

The painting’s creation was preceded by countless sketches. In the final piece, Podkowiński simplified the color palette, opting for black, brown, and grey, from which patches of white and yellow emerge. The woman portrayed in the painting was believed to be the object of Podkowiński’s unrequited affection, a theory further fueled by a shocking event at the conclusion of the A Frenzy of Elation exhibition.

On the morning of April 24, 1894, Podkowiński walked into Zachęta, requested a ladder from the janitor, and began to slash his painting with a knife. Twelve of the sixteen strokes were directed at the woman. The reasons for this destructive act remain uncertain – was it a consequence of unrequited love or the result of the artist’s deteriorating health?

Plagued by tuberculosis and allegedly a „terrible disease of the soul”, Podkowiński passed away a few months later, on January 5, 1895. However, thanks to Witold Urbański’s restoration of A Frenzy of Exultation in the same year, we can still admire the painting at the National Museum in Krakow.

„Woman Combing Her Hair” by Władysław Ślewiński, 1897

Sensual and subtle – that’s how you’d best describe Władysław Ślewiński’s „Combing He Hair”. The painting features a semi-nude woman seated on a bed, her side facing us. As she bends over to comb her long copper hair, an emerald duvet highlights the scene. A mirror lies on the bed, reflecting not the woman’s face, but a figure intently watching her – perhaps a hidden self-portrait of the artist?

Despite its lack of rich backstory, Combing He Hair carries a fascinating allure.

The identity of Ślewiński’s model remains a mystery.

Some speculate the intriguing figure to be a mythical mermaid, while others suggest she could be the Russian painter Eugenia Shevtsova, whom Ślewiński met during his stay in Paris and later married. Ślewiński painted several portraits of his wife, often capturing her in everyday situations.

The allure of Combing He Hair lies not just in its mysterious origins but also in its beauty and craftsmanship. Pay attention to the Art Nouveau lines, particularly visible in the silhouete of the model, which emphasize the softness of her skin and body. The tender expression in the painting makes us yearn for the woman to turn her head and share her gaze with us.

References:

- Dużyk J., Henryk Siemiradzki. Życie i twórczość, Wrocław 1984.

- Jaworska W., Władysław Ślewiński, Kraków 2004.

- Kozakowska S., Malarze Młodej Polski, Kraków 1995.